Malaysia’s Nutritional Anomaly

Historically, nutrition has always been a priority for the Malaysian government, beginning with the Applied Food and Nutrition Project and the School Supplementary Feeding Programme in the 1970s to the Rehabilitation Programme for Undernourished Children and the Healthy Lifestyle Campaign in the 1990s. Subsequent policy efforts have included the National Plan of Action for Nutrition of Malaysia (NPANM), with its first phase from 1996 to 2000 establishing Malaysia’s inaugural formal dietary guidelines. This was followed by NPANM II (2006-2015) and NPANM III (2016-2025), which aimed to continuously improve the nutritional status of Malaysians. Concurrently, the National Strategic Plan for Non-Communicable Diseases (2016-2025) was established to target conditions such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer, which are prevalent among adults who were once overweight as children.

Moreover, Malaysia enjoys a relatively stable food supply, supported by both domestic production and imports. Coupled with economic growth that has boosted household incomes – where average monthly household income rose from RM7,901 in 2019 to RM8,479 in 2022 – food theoretically should become more affordable for a broader segment of the population. In the 2023 Global Hunger Index, Malaysia reported a score of 12.5, indicating a “moderate” level of hunger.

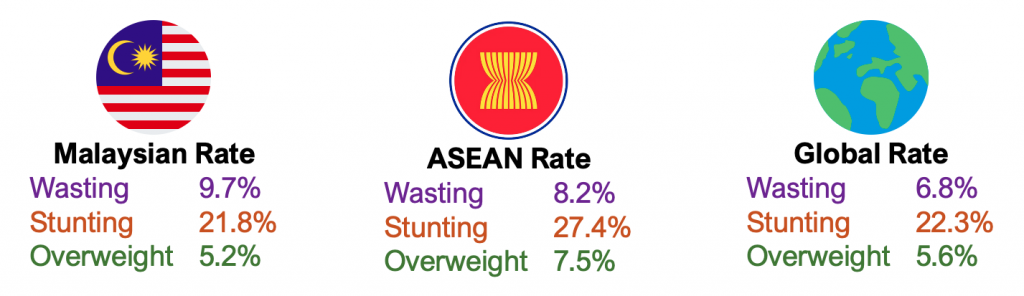

Despite a legacy of intervention and improved food access, a disturbing number of Malaysian children still lack proper nutrition. This begs the crucial question: Where is the disconnect? We have the policies and the resources, so why are Malaysian children still malnourished?

A Systemic Rot

The cause of the rot lies in the failures of the food, health and living environments.

Many children are trapped in failing food environments where the easy availability of cheap, processed foods outweighs the presence of nutritious options. This imbalance fosters poor eating habits from a young age, leading to both obesity and nutrient deficiencies. This is further exacerbated by the growing influence of corporations, whose commercial interests often take precedence over public health.

Dr Swee Kheng Khor, co-founder of the Malaysian Health Coalition, sheds light on this issue in an interview with the Global Institute for Tomorrow. He attributes the dominance of calorie-dense foods over calorie-healthy options in the food system to the influence of “Big Food” – large, multinational corporations that dominate the market. These corporations wield significant power, shaping dietary habits and food policies on a global scale. Dr Khor’s critique underscores the challenges of steering a profit-driven food system towards prioritising public health outcomes.

A common narrative argues that the issue of poor dietary habits is one of personal responsibility, suggesting that processed foods can fit into a healthy diet if consumed in moderation. However, a deeper look into the research on food marketing practices, the prevalence of food deserts where healthy options are unavailable, and the addictive properties of junk food reveals that environmental factors often overpower the natural mechanisms that regulate weight and health.

In addition to failing food environments, inadequate healthcare access and poor disease management also significantly impacts child nutrition. Children in failing health environments are more vulnerable to frequent infections and illnesses which can exacerbate existing nutritional deficiencies. Diarrhoea, in particular, further compromises the effects of often already inadequate diets, creating a vicious cycle of malnutrition. According to the World Health Organisation, children under three years in low-income environments experience an average of three diarrheal episodes annually, with each incident weakening their nutritional foundation, making it a major cause of malnutrition.

The challenge of addressing child malnutrition is further complicated by limited levels of health literacy, particularly among low-income demographics. Many busy parents and caregivers in these communities lack the knowledge necessary to meet their children’s specific dietary needs, hindering their ability to effectively respond to nutritional deficiencies. A recent cross-sectional study involving 2,983 low-income families underscores this issue. The study revealed that 89.5% of low-income adults themselves do not consume the recommended daily intake of fruits and vegetables. Furthermore, more than half of those surveyed (68.1%) reported consuming sugary beverages at least once a week. This knowledge and practice gap can perpetuate the cycle of malnutrition, as children are more likely to adopt the dietary habits modelled by their caregivers.

Poverty remains a pertinent factor as well, with a staggering 41% of households living below the national poverty line. However, it is not the mere fact of being in poverty that causes malnutrition, but rather the socioeconomic dysfunction that limits access to adequate nutrition for those in poverty. A recent UNICEF study paints a grim picture, revealing that nearly all children (95%) from low-income households experience relative poverty. The rising costs of living, particularly food prices, puts a tremendous strain on the budgets of 90% of Malaysian families, even with an increased average household income. The financial pressure is further intensified by the perception of declining financial security, with half the population reporting a worsening financial situation compared to just one year ago. Desperate families are forced into impossible choices, such as working longer hours, cutting back on essentials, and even reducing food intake.

Finally, failures in the living environment also significantly contribute to child malnutrition in Malaysia. A lack of safe play areas and facilities for physical activity can predispose children to obesity, particularly in urban settings where sedentary lifestyles are more common. Poor urban planning also limits access to markets selling fresh foods, making it more difficult for families to obtain nutritious ingredients.

Malnutrition in early childhood steals a child's future. Without proper food during this critical window, their brain development suffers, limiting their ability to learn, focus, and succeed in school and later on, in life – research shows that stunted children are proven to earn significantly less than their healthier peers. This isn't just about altering individual choices; it's about systemic change. We know the science – healthy kids need healthy environments. The question now isn't what – it's who? Who will step up? Policymakers? Businesses? Civil society? The answer: Everyone.

Ensuring every child gets the food they need isn't charity; it's a strategic down payment on a brighter future for Malaysia. Every nourished child is a vital brick laid in the foundation of a stronger, more prosperous nation.