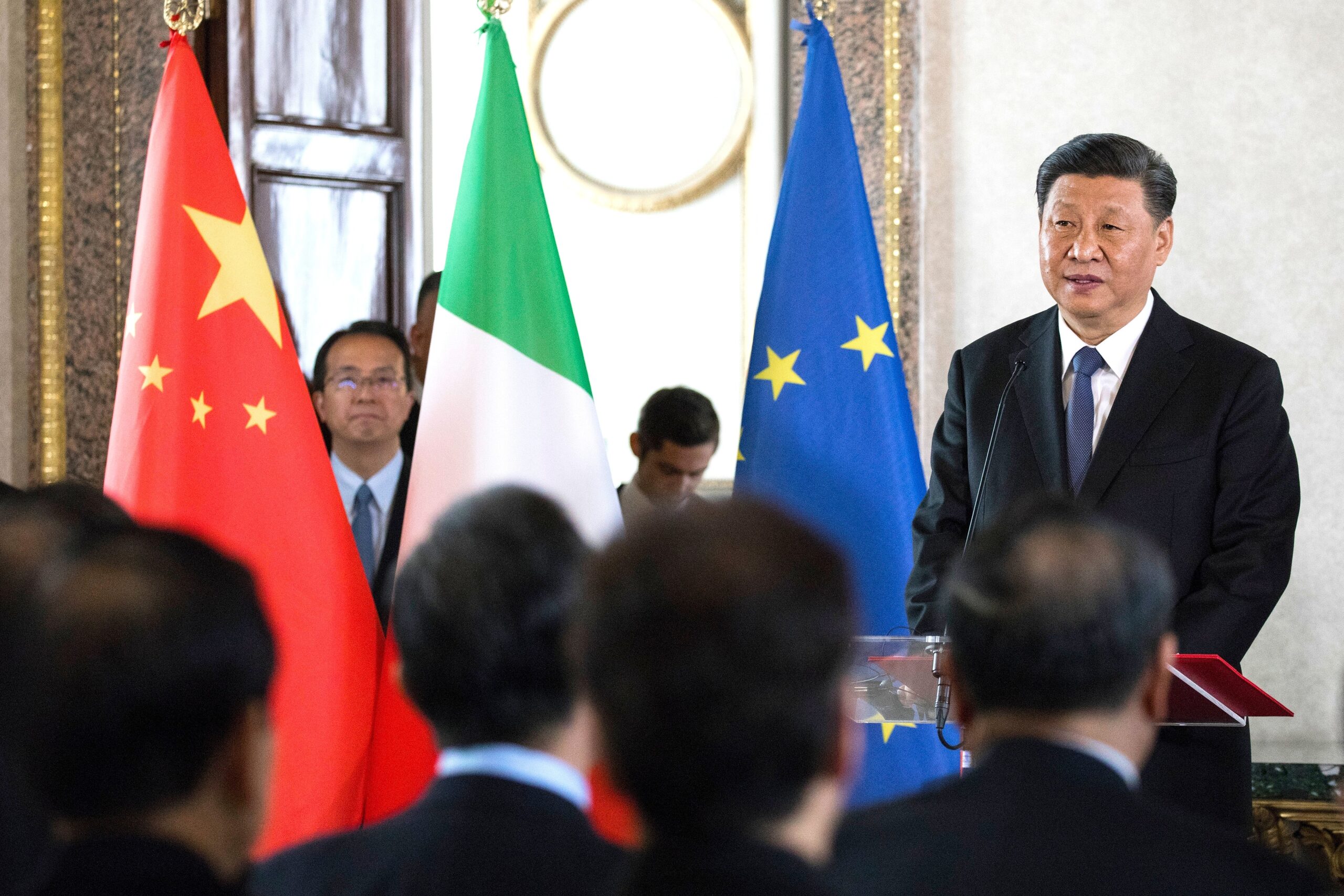

On 29 January, at Asia Society Hong Kong Center, I had the privilege of joining my friend Ronnie Chan, the Chairman of Asia Society Hong Kong Center, for a two-hour candid conversation where we explored the forces shaping China’s rise, its internal strengths and frictions, its expanding global footprint, and its distinctive governance model. The evening also marked the launch of my new book, Understanding China: Governance, Socio-Economics, Global Influence.

The room was filled to capacity with guests whose thoughtful questions reflected a clear hunger for deeper, evidence-driven discussion at a time when the world feels particularly unsettled. The event title, “Understanding China in a Fractured World,” was an apt one for the discussion. Here are some key points that shaped the conversation:

1. China’s model contains tangible strengths that many countries are beginning to recognise.

Across Southeast Asia, the Middle East, and Africa, people increasingly observe that “China is getting something right,” even if its approach cannot be easily duplicated. In my experience, this perception is quietly reshaping how elites around the world view China. Among the strengths most often cited are:

- The broad, reliable provision of national public goods.

- Lower crime rates leading to an invaluable sense of personal safety and social stability, which is priceless.

- Striking environmental turnarounds – such as the once‑polluted Yongding River in Beijing becoming clean enough for swimming.

2. Any weaknesses in China’s governance often stem from implementation gaps, rather than the misconception that power is concentrated at the top and repression is a tool.

I had the opportunity to clarify a common misconception that centralised authority is China’s primary vulnerability. In reality, many issues arise lower down the system, where delegated authority can be abused and misinterpreted – and great steps have been taken to rectify this.

I recounted an experience from Gansu, where local officials who constructed an extravagant government building were later arrested in an anti‑corruption campaign. Villagers whose land had been seized rejoiced when their property was eventually returned. Examples like this suggest that oversight and enforcement have strengthened considerably over the past decade.

3. China is institutionally more inclined than the US to use state power to confront systemic risks – from AI to the excesses of large corporate bad actors.

At a recent conference in China, tech entrepreneurs and experts treated my questions about AI’s social risks with remarkable seriousness and intellectual openness. Their engagement stood in stark contrast to what one often encounters in similar gatherings in places like the Silicon Valley.

China’s political culture, with its greater emphasis on meritocracy, performance legitimacy, communitarian obligations and the state’s duty of care, makes it more prepared to impose stringent regulation when necessary. By comparison, the US system operates under the constraints of overwhelming corporate capture, and often finds it difficult to counterbalance powerful private interests.

Understanding China is a take on the aforementioned themes and aims to offer a clear, accessible, and non‑ideological framework for making sense of China.

Order the book:

Chandran Nair

Chandran is the Founder and CEO of the Global Institute For Tomorrow (GIFT), a pan-Asian think tank dedicated to helping organisations navigate global complexities. His work focuses on the shift of economic and political influence to Asia, the evolving role of business in society, and the transformation of global capitalism.