Six billion Asians living like Americans and Europeans is impossible – there is not enough to go around

Chandran Nair

“

The Muslim call to prayer for me is the most spiritual call and so when I see Muslims, I see them as brothers and sisters. In the evenings, we’d go and eat char siu bao and noodles. I learned to eat with chopsticks from the age of three.

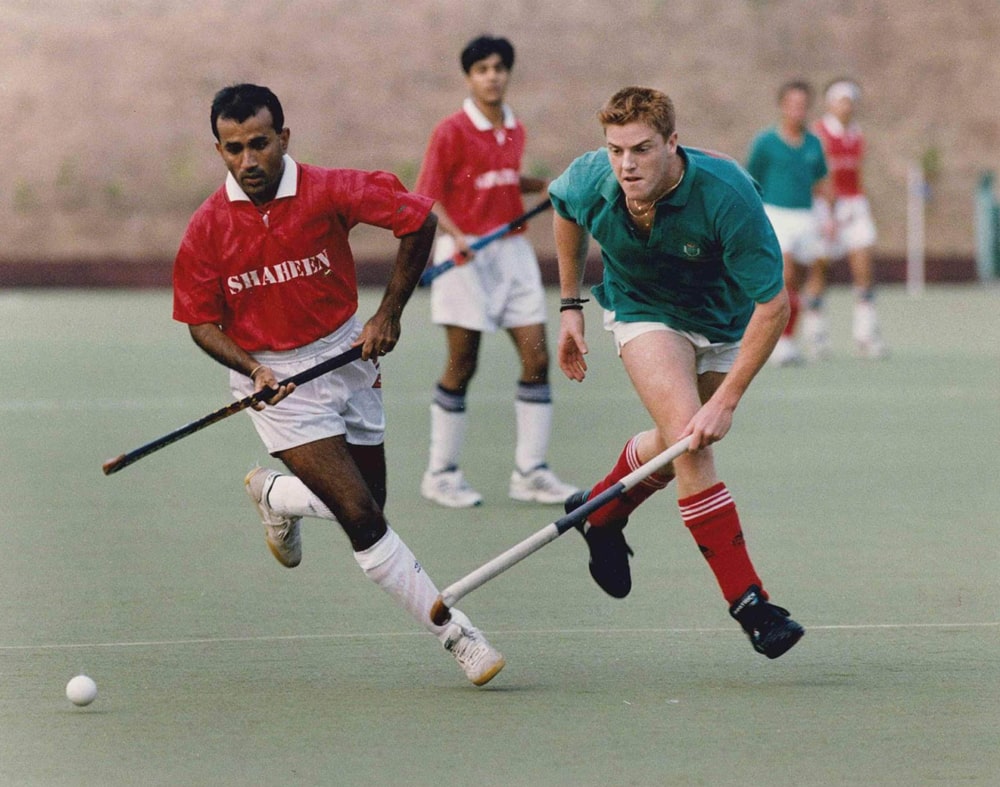

Olympic dreams

Two of my neighbours were ex-Malaysian hockey Olympians and we looked up to them. One of them gave me a stick when I was 10. Every day from 4pm to 7pm, 10 of us kids played hockey on a stony patch of grass near our home. That was the highlight of my day, I was obsessed with hockey.

I played for Malaysia’s under-20 hockey team and aspired to play for the national team. I had a chance of maybe representing the country at the Olympics but made the decision that my education was more important.

The Malaysian education system at the time was tough. There were only three or four universities in the country, and I didn’t have the grades to get in, so I borrowed money from the bank and was accepted by Reading University in Britain to read biochemical engineering, which was a new subject at the time.

Aged 20, I arrived in London on a one-way ticket – my first ever flight – and was surprised to see white guys doing manual labour. In the colonial setting the white people were always the bosses.

Water Works

My degree was a four-year sandwich course and I didn’t see my family in that time as I didn’t have the money to fly back. I got a scholarship for the last two years; I think I got it by talking smoothly, I learned to sell at an early age.

I graduated in 1980. There was a lot of research money going into ultra-pure water systems and I smooth-talked my way into a job in one of the leading companies in the UK, Permutit-Boby, based in Hounslow, London.

I worked there for two years and got a lot of experience in both design and engineering and also the research side, and I paid off my student debts. As a student, I’d met a lot of people from Africa, particularly South Africa and Zimbabwe, and I got involved in the anti-apartheid movement.

The US would do well to remember that there is value in embracing different political systems for a more equal world. Why? Because China has demonstrated that a nation does not need to meet the West’s definition of “democracy” to achieve success for its people.

This is because democracy is not defined by simplistic notions about free speech or Western electoral processes. Democracy is the right of all peoples, and cannot be arbitrarily judged by the US.

According to the United Nations Charter: “The UN does not advocate for a specific model of government but promotes democratic governance as a set of values and principles that should be followed for greater participation, equality, security and human development”.

This is to say that the political systems of a country and its method of governance are important because they must ultimately serve the people, enable them to have a sense of participation, satisfaction and improvements to their quality of life. Democracy is just one approach to this, so it is reasonable to conclude that China has developed a successful governance system suited to its culture, history, and the needs of its population.

Nair as CEO of the Global Institute for Tomorrow receives a personal endorsement for his Global Young Leaders Programme from former United States President Bill Clinton at a Clinton Global Initiative event. Photo: Courtesy of Chandran Nair

My focus shifted from simply getting a job to thinking about what this technology is for – when three-quarters of the world didn’t have access to the basics in water supply what the hell was I doing treating water for nuclear reactors and pharmaceutical plants?

I got a job as a volunteer in southern Africa to build rural water systems and sanitation facilities and link that to community health development. I was very idealistic. My parents were horrified. The idea of leaving the UK after I’d got a work permit was unthinkable to most people. That was supposed to be the passport to your future, and I gave it up.

Going underground

As a Malaysian citizen at that time, I couldn’t go into South Africa because Malaysia was one of the few countries in the world that didn’t recognise the country, so the closest place I could get to and help with development was Swaziland, which bordered South Africa and Mozambique.

The Amazon model is the best example of a broken system – it is essentially saying you can have anything you want, and we will make it so cheap … We call that innovation, it’s actually destruction

Chandran Nair

“

The International Voluntary Service placed me with the Rural Water and Sanitation Board, and I was given a stipend of what would be HK$250 a month, and housing and a truck to take workers and materials to sites.

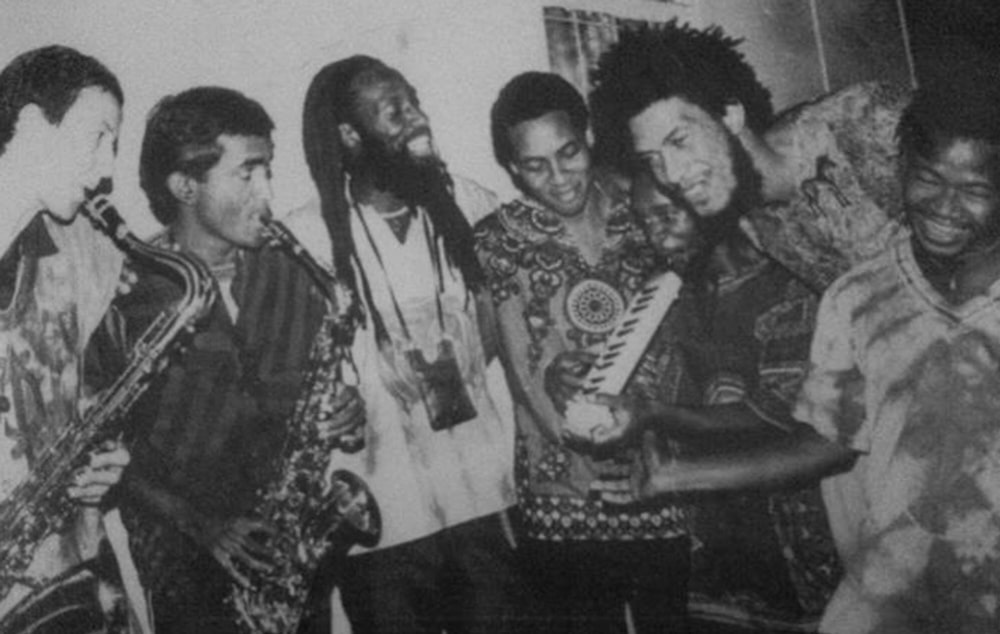

I’d learned to play the saxophone in London and within a few months in Africa formed a band called Imphandze. We were a jazz reggae band and talked a lot about freedom and the end of apartheid. It became a successful outfit and we even cut a CD and were invited to play in Soweto.

I crossed the border on a forged passport. I was approached by the anti-apartheid underground movement, which was essentially helping leaders in the movement who were on the run. I was recruited and provided safe houses and sometimes took messages into Mozambique.

Firsts in Asia

In 1985, I decided to come back to Asia and applied to do a master’s degree in environmental engineering at the Asian Institute of Technology, in Bangkok. When I finished that, I joined a Thai-American engineering firm called Siam Tech in Bangkok as an engineer and within a year was made managing director.

A few years into that job, I was speaking at a conference in Thailand when the managing director of a global sustainability consultancy, Environmental Resources Management (ERM), approached me. It took a little persuasion but, in 1990, I accepted a job with them as a senior consultant. It was the best decision I ever made.

I thought it was a good deal – I had less responsibility and was making more money. I don’t play office politics, I’m not competitive in that way, but within a year I was the managing director. Within the next five years, I grew the company from 10 people to about 100 and over the next 10 years opened offices in 12 countries.

I’m very proud I opened the first environmental consulting firm in China and in Vietnam, Japan, Korea, Malaysia and Singapore.

Unsustainable developments

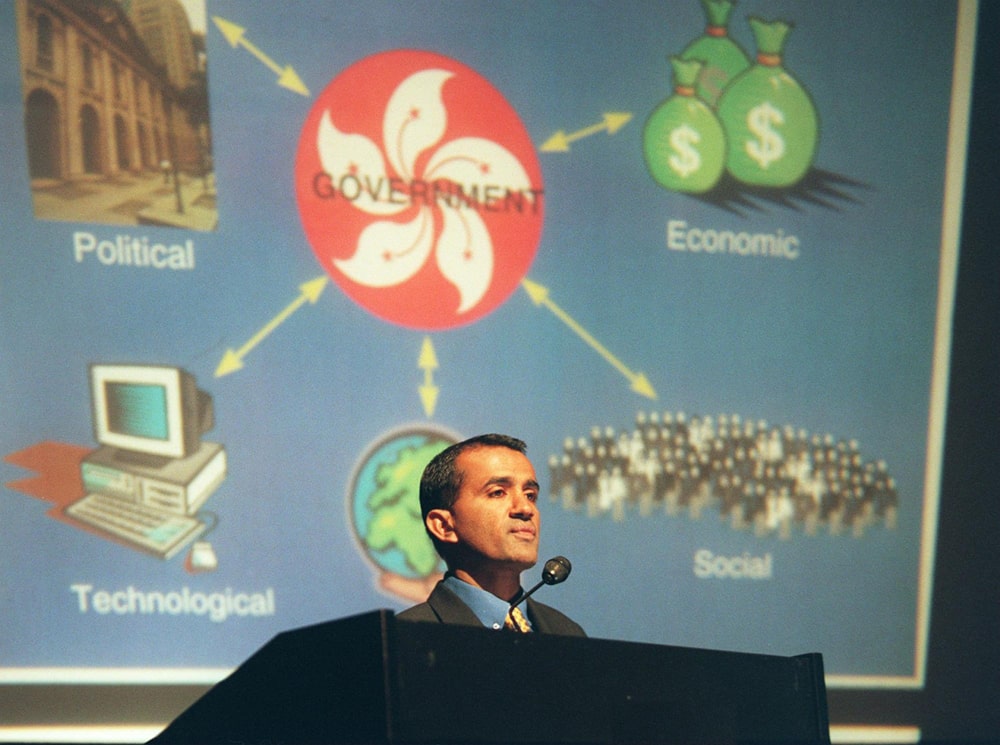

I led a study in Hong Kong that led to the first decision framework for sustainability for any city in the world – that was completed in 2003. The government attempted to do it, but it was so far-reaching in its implications for making decisions and framing the sustainability of decisions that it needed bold administrative institutions to be able to accept that.

I was one of six people on the main board of ERM and the only Asian. We did a management buyout. I got so disillusioned and was at odds with most of my board members, particularity in terms of geopolitics, wars. Typically, you serve on a board by not having any political views, and so you become dishonest, you are in denial.

All of us know what’s going on, but we are supposed to keep quiet. People on boards hire people they know, no one is supposed to say anything and constantly they get caught out because there is no moral framing of understanding.

East is East and West is West

After 14 years with ERM I left, I wanted to go on a different intellectual journey. I was flabbergasted that we in Asia invite a bunch of ill-informed Texans from [a think tank] called the Heritage Foundation to come here. You know how imperial that is? A bunch of guys who know nothing.

Then there’s the Chatham House guys and the Brookings Institution. So, I said, “When are we going to have our own narrative?” My ambition was to start an independent pan-Asian think tank and I founded the Global Institute For Tomorrow (GIFT) in 2004.

I felt that Asia was essentially asleep at the wheel. I saw there was a power shift from the West to the East. What is important from the sustainability point of view is that Asia’s population will be six billion around 2050 or 2060.

Six billion Asians living like Americans and Europeans is impossible – there is not enough to go around. Yet we are being told there is one economic model – the Western model of capital markets and consumption.

The Amazon model is the best example of a broken system – it is essentially saying you can have anything you want, and we will make it so cheap that people can essentially order three things, use one and throw the other two, and it’s cheaper than last year. We call that innovation, it’s actually destruction.

The entire economic model that the world has embraced is one that does not internalise the true cost of consumption and that has ramifications in terms of inequality and disenfranchisement. Carbon dioxide is just the tip of the iceberg in terms of that overconsumption model. I can say this because I’m not the guy from McKinsey. We are independent – I don’t take money from anyone.

We talk about the substantiality issues of consumption, pricing and government systems. When I talk to pharmaceutical companies, I talk to them about how they have to adjust their world view. You can’t sit in Europe and understand Asia without changing your entire structure. You cannot say you believe in diversity and inclusion, which is essentially tokenism, when your entire structure is led by a bunch of Westerners who have no connection to this part of the world.

Extended family

I’m single. I think marriage and children are hugely overrated, it’s just not for me. I support a lot of family – my nephews and nieces; I try and give advice and support where I can. I also have an extended family of people I try and support in Malaysia, migrant workers and people in Nepal, China and the Philippines.

I’m proud that through a little of my help at least two or three families have for the first time got kids going to university and I try and encourage them to study science or engineering.