Frantz Fanon is one of the key non-American thinkers on this subject, whose works sparked much of postcolonial studies and critical theory. As early as 1952, Fanon argued that the colonial project left no part of the human person and the human experience untouched. His 1961 magnum opus, The Wretched of the Earth, is a full examination of how colonialism affected societies; he describes his taxonomy of the colonized, which includes the “worker,” the “colonized intellectual,” and the “lumpen proletariat.” The colonized intellectual is the middleman between the colonizer and the colonized, trading in the cultural capital of the colonial power without ever getting to be a part of it. An example is that of elites from Asia studying in Ivy League schools and then seeking jobs in the leading Western corporations, especially in investment banking or finance, which are made out to be the most sought-after careers.

Fanon’s work sparked further extensions of critical theory throughout the world, with one particular development being the creation of “critical race theory,” which applies critical theory to racial issues in the United States. First developed in the mid-1980s, the theory has two particular tenets:

1. Legal systems play a role in preserving and maintaining systems of racial supremacy.

2. The relationship between law and racial power needs to be transformed in order to achieve an antiracist agenda.

However, this is an understanding of race, racism, and structural discrimination that is born out of an American context and its particular history with race and race relations. It does not examine the use of White power on a global scale and over centuries to dehumanize and oppress other nations for economic gain.

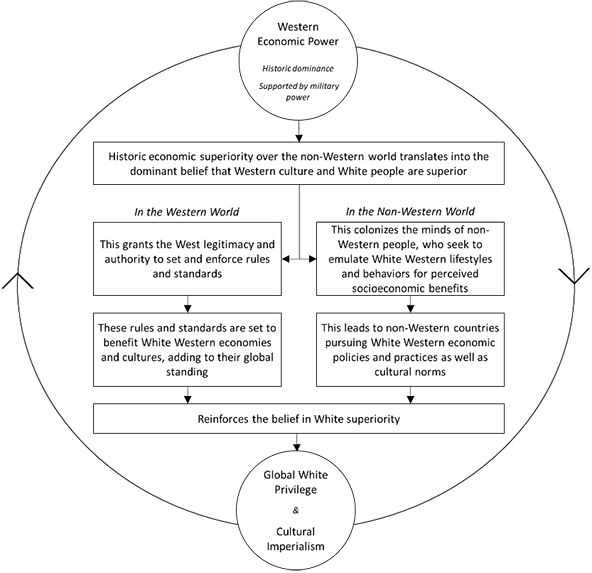

Race as a concept generally does not feature in mainstream discussions of global governance and international relations. Some theorists try to apply racial dynamics seen on the domestic level to the international sphere—for example, how racial inequality and social unrest affect perceptions of countries overseas and thus impact a country’s “soft power.” Race is conveniently ignored in providing explanations as to why only an American or European can head up the World Bank or the IMF. That racism defines the way two of the world’s most important multilateral agencies are governed is rarely if ever discussed in the open.

Although few theorists use the explicit framing of race to understand how countries and societies interact with each other and how power is exercised, there is far more discussion of how we talk about and understand the way the world reinforces Western privilege. Within the realm of academia, there is some criticism that Western Europe and North America are portrayed as the places “where things happened,” whereas the rest of the world merely adopts Western innovations and reacts to developments happening elsewhere.

More broadly, much of postcolonial thought analyzes how colonial domination persists through current global institutions and the global security framework. Such aspects as the global network of American military bases and the global debt structures for developing countries are seen as continuations of colonial and imperial dominance rather than active preservation of Western dominance.

But why has the insight of critical race theory—that laws, social structures, and cultural norms perpetuate White privilege—not been applied on the global level?

One possibility is that global governance and social structures are evolving in the post-colonial era as differences between countries become more obvious and there is no clear consensus yet for a post-Western world. As I noted in my book The Sustainable State, global governance and international law often rely on states to do the work for them, meaning that when global and national interests collide, national interests usually win out. This means that the usual analytical focuses used to address structural racism—laws, regulations, and institutions—are less strong on the global level.

In addition, the traits and behaviors of different ethnic groups are often conflated with national governments, which can complicate the search for causal factors. For example: Are assumptions about ethnic Koreans based on assumptions about Koreans as an ethnic group, or motivated by actions of the South Korean national government? This brings in discussions of international relations and national security, which complicate (but do not preclude) any discussion of structural racism.

Finally, another potential reason why critical race theory has not been applied as much outside the West, at least in domestic contexts, is that non-Western countries have often dealt with race and ethnicity more explicitly in legislation, in both positive and negative ways. For example, Malaysia practices affirmative action for the Malay majority, providing privileged access to positions in all areas of the economy as well as in both the civil service and state-run enterprises. There is much analysis about racial politics and racial discrimination in Malaysia, but the explicit use of racial and ethnic categories in legislation means that there is little “need” to uncover more structural and implicit discrimination.

Yet the application of contemporary critical race theory and other insights from the academic discussion of structural discrimination would help to reveal much about how privilege operates on the global level. Why do Western governments and institutions who represent a small minority of the global population have so much say in what happens around the world? Why do those who lead them assume automatically that they have a right to get involved, have a role to play in solutions, and have all the answers? And why are their solutions automatically assumed to be the best?