How Asia Can Plug Into the Agritech Revolution

1. Establish Better Digital Connectivity in Rural Farming Areas

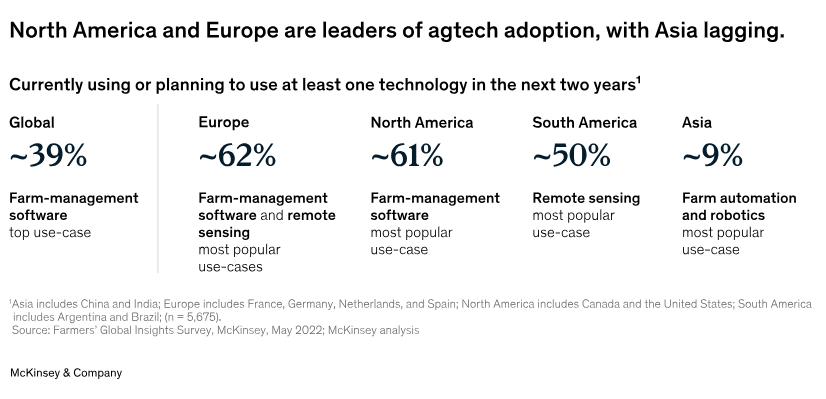

In order to use much of the AgTech solutions currently on the market, wireless internet access, digital infrastructure and connectivity is a pre-requisite. However, in many rural areas where farms are typically based, particularly in Asia, connectivity is inadequate and potentially non-existent. This is less of a problem in the west, where 85% of farms in US have access to internet compared to just 46% in Asia. This may explain why more farms in North America and Europe are using AgTech compared with those in Asia. To close the AgTech gap between Asia and the West, the digital infrastructure needs to therefore first be put in place in these regions, so that the AgTech solutions are actually viable for use. This is something that the local famers have little to no control over, so this is the responsibility of the government and policy holders to ensure that connectivity in these farms is accessible and appropriate for AgTech solutions.

2. Provide Accessible Formal Financing Options

Now that the digital infrastructure is put into place, farmers can start to consider AgTech solutions but now they can a different problem – where do they obtain the finances to purchase AgTech?

Compared with the US where there are substantial subsidies for the agricultural sector (USD $11.18 billion was paid out to US farms between 1985 and 2023), many of the farmers in Asia are smallholder farmers with little access to financial services. In fact, less than a third of the financial demand for smallholder farmers in Southeast Asia is being met. Without heavy subsidies, many of these smallholder farmers in Asia simply cannot afford to purchase the AgTech that they need in order to improve productivity and output.

Whilst it may appear that agricultural subsidies would solve this problem, it is also important to note that agricultural subsidies need to be focused on sustainable production of nutritious crops as highlighted in this report by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN. At present, subsidies are skewed towards “cash crops” (crops planted for the purpose of selling on the market for profit) rather than food crops (food crops: planted for sustenance). In fact, solutions were proposed by GIFT during the Malaysia Stay and Build 2023 programme on this very subject.

For the adoption of AgTech to be successful in meeting the demand for food security, there is a need for balance between the production of cash crops and food crops – with a keen emphasis on the latter as opposed to the former – as highlighted by ICRISAT-Nairobi. Subsidies must therefore be carefully considered to ensure that the agricultural production is sustainable and does not contribute to waste.

A solution that may be more relevant at the farmer level, are specialised agriculture finance apps, with AgTech startups aiming to bring financial inclusion to Asia’s farmers. These startups aim to bridge the gap between smallholder farmers and financing which will consequently enable farmers to afford other AgTech solutions to improve their farming operations.

3. Different Solutions for Different Spaces

An important consideration to what AgTech solution can be adopted for Asian farmers, is the size of their farms. The average farm size in north America in 2023 is 464 acres, whilst an average farm size in Asia is less than 5 acres. Whilst farmers in North America can make use of large scale machinery, these are not possible in Asia where land is at a premium and farm sizes restricted.

This doesn’t mean that there aren’t solutions for small farms, solutions for smaller spaces include those such as vertical farming, where farms are built vertically and use digital technology to monitor and grow the produce. However, this is a solution that may be useful in rich cities but is of less relevance for farmers in Asia who can ill-afford such luxuries, where they want to make use of their fertile land.

Other solutions include the use of agricultural drones to conduct crop monitoring and targeted application of fertiliser. Operated remotely, these drones minimise the environmental impact associated with traditional methods and their precision helps combat fertiliser overuse and run offs which lead to pollution.

Making use of the rapid growth of smartphone penetration, there are also specific smartphone apps available for farmers, such as Syngentas Cropwise Grower which allows farmers to quickly diagnose crop diseases and provides treatment advice.

These solutions may not be well known and would require training, education and collaboration with the local farmers to find the best way to implement digital technologies to enhance their best farming practices. Perhaps the most important thing to take note is that topographical differences between Asia and the West require different solutions.

4. Post-Harvest Considerations

Whilst digital agriculture technology can be used to enhance existing farming practices to improve farming output and increase productivity, what happens post-harvest also needs to be considered. More crops being harvested means more crops need to be stored, managed and transported to the consumer before they go to waste.

Despite increasing pressures on food supply, about one-third of the total amount of food produced for human consumption is wasted globally. In Asia, more than 40 percent of this loss occurs throughout commodity supply chains at the post-harvest level—between harvest and the consumer. In Vietnam, post-harvest losses are estimated at 20-25 percent for fruits and more than 30 percent for vegetables. In Cambodia, this is even higher.

Digital technologies to improve the post-harvest process would therefore be just as important as technologies used to increase production and quality. Schmidt et Al. do a wonderful job of identifying the digital solutions for post-harvest in this paper. In essence, there are many components of the post-harvest process and each component may incur some loss, these can be minimised using digital monitoring and control solutions, however there is still room for improvement, something that the AgTech companies will need to work with local farming communities to attain the solution.

Conclusions

Current farming practices fall short of meeting the food demand of the world and in particular the 1.1 billion people in Asia who face persistent food insecurity. Highly dependent on the climate, the agricultural sector in Asia needs to be highly adaptable and resilient towards external threats and disruptions. For Asia, the world's agricultural powerhouse, embracing digital solutions is no longer optional. Integrating appropriate AgTech throughout the farming process, from crop production to post-harvest management, holds the key to unlocking significant improvements in food security.

This critical challenge lies at the heart of GIFT's upcoming Global Leaders Programme (GLP). In partnership with industry leader Soma Group, we will be tackling digital agricultural solutions specifically tailored to Cambodia's needs. However, the learnings and innovations fostered through this program hold the potential to be replicated throughout Asia, offering a scalable model for regional food security.