Even after the predictions telling us that Typhoon Mangkhut would be an unusually severe storm, it is likely that no one expected it to be as serious as it was. Mangkhut was the most intense storm since records began, with the highest wind speeds and storm surges ever recorded. And it has had some of the largest impacts: the number of emergency calls was five times higher than last year’s super typhoon, and the insurance bill from property damage will likely dwarf any previous storm at US$1 billion. Then add the multiple days of school closure and public transport disruption, and it’s clear Mangkhut is a storm for the history books.

Mangkhut has been more devastating than our last signal No 10 typhoon – Hato – which hit last year, or the one before that – 2012’s Typhoon Vicente. The last three signal No 10 typhoons, all strong storms in their own right, have happened in the past six years. These storms are most likely to become stronger and more frequent.

The flooding in Hong Kong’s coastal areas should be a reminder that the city has not implemented any plans to deal with the effects of climate change. It has not built sea walls, nor changed building codes for coastal buildings to account for storm surges, nor protected critically vital utilities and infrastructure to withstand extreme weather.

It’s true that Hong Kong handles typhoons better than most places and that is to its credit. The city will likely be back to normal operations after another day or two. The hardworking and honest endeavours of residents was on full display in the aftermath of Mangkhut – the city at its best. The Observatory should be credited for their clear and honest warnings about Mangkhut, meaning that people were ready for what was to come.

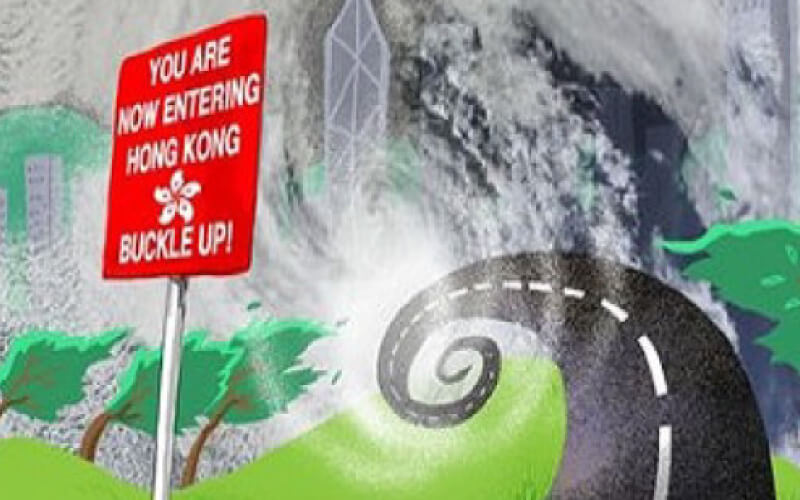

But if storms as strong as Mangkhut become a regular occurrence, Hong Kong needs to be much more resilient in the face of extreme typhoons. It will happen again as night follows day: Hong Kong after all sits at the end of a “typhoon super highway” through the Philippines and Taiwan.

Yet Hong Kong’s government and legislators do not appear to be treating our ability to withstand the effects of climate change and extreme weather as our most important long-term policy concern. It does not feature in our city’s politics to any extent, despite the fact that both sides of the political divide likely agree, at least in principle, that climate change presents a threat to the city. It is unlikely that a debate will be had in the Legislative Council now, attended by all, to discuss the implications of what happened this week and what major adaptation polices need to be considered.

Singapore – a country less at risk from extreme weather patterns – is already investing in new sea walls and strengthening building codes to account for rising sea levels. In contrast, Hong Kong’s political system does not seem to be able to focus on these sorts of existential threats and make the long-term policy decisions needed for what the future holds.

In some cases, the solutions proposed by the government are actually less resilient than doing nothing. The solution favoured by the government to the issue of affordable housing is to reclaim more land on Lantau, Western Kowloon and the New Territories. A pro-establishment think tank has gone further in calling for an artificial island to be reclaimed in between Lantau and Hong Kong Island.

Yet expanded reclamation makes more low-lying areas susceptible to flooding from storm surges. And if these reclamations are meant for large public housing projects, then the government is potentially putting thousands of people in these areas at risk of coastal flooding.

Yet the irony is that within the government, there are highly qualified professionals who have the scientific background and expertise to provide sound advice on the policies that are needed to adapt to a changing world. Sadly, they appear to have been ignored for political reasons. That in itself is a telling indicator of institutional capture by vested interests.

After all, it is well known that an artificial island in open seas would be even less resilient to the effects of extreme weather. How easy would it be for emergency services to reach the island if a typhoon causes a major crisis? How easily could people evacuate on short notice? How quickly would public transport recover?

Of course, it is possible to reclaim land in a manner that can withstand rising sea levels. But this has major implications for surges in surrounding populated areas. It also ultimately makes the project more expensive: experts predicted that the cost of an artificial island would double if it was built to withstand rising sea levels and extreme storms.

Despite the increased costs and greater risk, the Hong Kong government is still pursuing land reclamation as the only possible option to solve the housing crisis, because the kind of short-term policy that ultimately affects no interest group is the only kind of policy that can make it through Hong Kong’s broken political process.

Over the next few days, Hong Kong’s excellent public services will clean up the debris from Typhoon Mangkhut. There may be some new systems implemented to prevent some of the disruption from the next storm that hits. But a city as densely-populated, as globally-important and yet as threatened as Hong Kong cannot afford to be reactive. It needs a major rethink so that it is prepared for a very unpredictable and precarious future on the “typhoon superhighway”. And that means more than asking residents to wear crash helmets and to fasten their seat belts.

More typhoons like Mangkhut can be expected as oceans get warmer, and they are likely to be more frequent and stronger than we ever imagined. And do not rule out a direct hit.

Hong Kong’s political system needs to get its priorities right – less fuss about extensions to the homes of government officials, for example – and start developing a long-term plan to make this great city adapt to weather patterns that will increasingly go amok with potentially catastrophic consequences.