I recently attended a conference in France, near Mont Blanc, where I was invited to comment on a discussion about the beauty of experiencing what mountains have to offer – how they affect people who have the opportunity to ‘enjoy’ them. Attendees at the conference, many of whom are avid mountaineers or lovers of the joys of experiencing wilderness, spoke to the spectrum of positive impacts that being in mountainous landscapes confers: exercise, fresh air, a closeness to Nature that cannot be explained by mere words, bonding with peers in ways that are often not part of daily life, a sense of freedom and even a meditative and spiritual effect. The discussion moved towards the importance of finding ways to make mountains more accessible to those without the means of exploring them.

My response to this somewhat broke the reverie: is it not time that humans consider leaving mountains – and more broadly wilderness – alone? Is it not time that humans, who now number eight billion, act intelligently to enable a managed retreat from Nature? Don’t we already know from our collective scientific data that the assault on Nature and the biosphere is a direct result of our inability to respect limits and boundaries in search of economic growth, to feed our curiosity, or to satisfy our desire for pleasure? And is it not the most privileged of us who are the biggest culprits?

The time has come to start the process of respecting what we do not quite understand, and instead enjoy mountains – and all aspects of wilderness – from afar, just knowing they are there. We have been justifying further incursions with dubious arguments about the need to get in touch with Nature – we have literally been in touch with Nature for too long and have trampled upon it irreversibly in many parts of the world – or to conduct more research to understand it better for the purpose of protecting these places from “other, less caring humans”. We have to honestly acknowledge that we already know and have had enough experience of Nature to act to protect it through a managed retreat, and not from just the most precious regions of the world, but also from many areas where our presence does not add any value to Nature or humanity. We need to completely recalibrate our relationship with Nature and the wilderness with regard to our preoccupation with the notion that we have a right to enjoy it like any other commodity. And that means rejecting the idea that just because one can afford to travel to places of natural beauty, one is entitled to awe and pleasure.

This speaks to a broader issue, which is the relationship that many modern and wealthy societies have with Nature: to exploit it, to seek self-gratification through it, and to want to own it, even if only temporarily. It is a contradiction that is steeped in outmoded ways of seeing the world, in convenient denial, through elaborate justifications that enable an elite minority to trample and pave the way for abuse and destruction, while also appearing to be ‘lovers’ of Nature.

In the west, many factors have contributed to this status quo. Most obviously, the rise of capitalism, but also, historically, the Enlightenment belief of exploiting Nature for humankind’s betterment and the historic Judaeo-Christian rationalisation of creating dominion over Nature as per certain (but not all) religious thought: “Go forth and multiply”; “Everything that lives and moves will be food for you.” Collectively, this has cultivated the need to dominate wilderness for a sense of conquest, or the desire to escape and seek refuge away from society.

With all the evidence of human transgression of natural limits (for example, the nine planetary boundaries), it is time to have an international effort to foster new levels of self-awareness surrounding the relationship we share with Nature, especially if we are to preserve ecosystem integrity and not fall into neocolonial traps – even those that arise from a seemingly positive place, such as seeking to enjoy mountains and the wild. A retreat from Nature and wilderness is now overdue.

Cultures across the world have maintained spiritual or holy relationships with mountains and the wilderness for thousands of years. The First Nations of North America are renowned for such relationships, historically having practised a communal approach to land ownership that was starkly at odds with the capitalist private land ownership model of European colonialists. In northern India and Tibet, Mount Kailash – near to the source of the Indus, the Sutlej, the Brahmaputra and the Karnali rivers – is sacred to four religions (Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Bon) as the spiritual centre of the world, and attempting to climb it is therefore forbidden, an edict that stems from a place of deep respect.

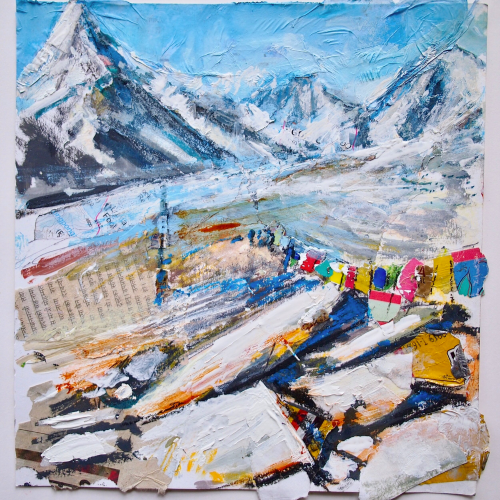

However, the value placed on mountains by communities is not always respected by those from richer societies. A significant point of origin lies in colonial conquest and the establishment of settler communities, who by definition were trespassers and had no respect for local traditions and the beliefs of Indigenous communities. There are two poignant examples: Uluru and Sagarmāthā/Chomolungma (colonially renamed as Ayers Rock and Mount Everest respectively. Uluru, in central Australia, is sacred to the Anangu, the First Nations peoples of the area. They do not climb the monolith. Yet ever since white settlers arrived, tourists (including the late Queen of England and the current King) have summited – despite pleas to prevent them. Fortunately, climbing was eventually banned – but not until 2019.